This is the first of three blog posts I will be writing about my current research on the causes and consequences of disparities ragweed pollen in urban areas. Read on!

Why ragweed!?

As an urban ecologist, I am interested in how urban environments shape the distribution and traits of plants and animals. When I began my PhD in 2013, I spent a few weeks walking around Minneapolis identifying different species and observing urban habitats. I quickly noticed that there were a few plants that thrived. One of these plants was ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), the bane of many allergy sufferers. Ragweed produces a prolific amount of pollen, causing allergies in approximately 15-20% of Americans, and triggering asthma in some individuals. If you have allergies in late summer or fall, you are probably allergic to ragweed!

Curious observations

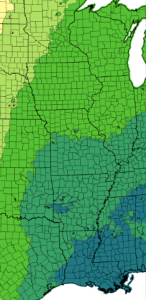

I found ragweed just about everywhere: along bike paths, railroads, and riverbanks and in sidewalk cracks, lawns, parks and vacant lots. I also noticed that ragweed wasn’t evenly distributed across Minneapolis. Some residential neighbourhoods had lawns and boulevards with few ragweed plants and lots of trees. Others had more vacant lots and recently disturbed areas, fewer trees, and more ragweed plants. These two observations (ragweed growing in lots of different habitats, ragweed distributed unevenly across the city), led me to focus my dissertation on studying how selection in response environmental variation at different spatial scales (within a city, between urban and rural areas, and across latitude) can shape the evolution and adaptation of plants.

As my research took me to other U.S. cities (St.Louis, New Orleans, and others), I continued to observe differences among neighbourhoods in the abundance of ragweed plants. Was this a real pattern or simply an observation? Why might some neighbourhoods have more ragweed than others? And does this lead to differences in the amount of allergenic pollen across neighbourhoods? My dissertation research went in one direction, and these questions were left percolating in the back of my mind.

Is ragweed pollen in urban areas an environmental justice issue?

Fast forward to 2018: I was writing a research proposal for the Grand Challenges Postdoctoral Fellowship. The goal of this fellowship is to encourage interdisciplinary research that contributes to addressing major societal challenges identified by the University of Minnesota. My observations about the disparities in the abundance of ragweed in cities seemed like a good fit because I was increasingly realizing that it might be an environmental equity issue.

By now I had learned that most cities only have a single pollen count, but in New York and Detroit, the amount of pollen produced by trees and weeds can vary at scales of 1-10 km. This indicates that wind-dispersed pollen like ragweed may not move as far in urban areas as expected. Single pollen counts may not be representative of the actual pollen levels in different neighbourhoods. Ragweed is also more abundant in vacant lots in Detroit, and vacant lots are more common in lower income neighbourhoods Furthermore, wealthier neighbourhoods tend to have more trees or canopy coverage, which likely reduces the available habitat for weedy species like ragweed that tend to thrive in recently disturbed areas.

I decided to step out of my comfort zone and proposed to study the environmental and societal causes of inequality in urban plant allergens by diving into the fields of mathematical biology, public health, and environmental policy. I was fortunate to find three mentors (Dr. Allison Shaw, Dr. Bonnie Keeler and Dr. Jesse Berman), who were equally enthusiastic about these questions. In 2019 I was awarded the Grand Challenges Postdoctoral Fellowship for 2019-2021 to pursue this research.

Up next: pollen traps, field surveys and lots of ragweed

In the coming weeks I will be writing updates for two components of this research I’ve started working on in 2020:

1) Measuring ragweed pollen at small spatial scales in Minneapolis using pollen traps

2) Assessing the abundance of ragweed plants and green amenities using field surveys.

Stay tuned!